—Photographs: Joji Hashiguchi

—Design: Kumiko Otsuka

—Support: Team N.Y.

—Texts: Yoshitomo Nara, Mika Kobayashi

—Printing Specialist: Motoyuki Kubo, Joji Hashiguchi

—Production Assistant: Yasuyo Takahashi

—Translation: Daniel González

—Edit: Keenan McCracken

—Printing Director: Linus Lee

—Printing: Pristone

—First Edition 2020

—Edition of 1,000 copies

—ISBN : 978-0-578-42908-3

—Page: 256 pages

—Format: 210 mm x 290 mm

—Photograph: 139 black and white photographs

—Printing: duotone press black and white images with vanish

—Paper: Symbol Tatami Ivory 135 gm

—Cover: 350 gm paper duotone with white foil stamp and PP matt coating

Joji Hashiguchi

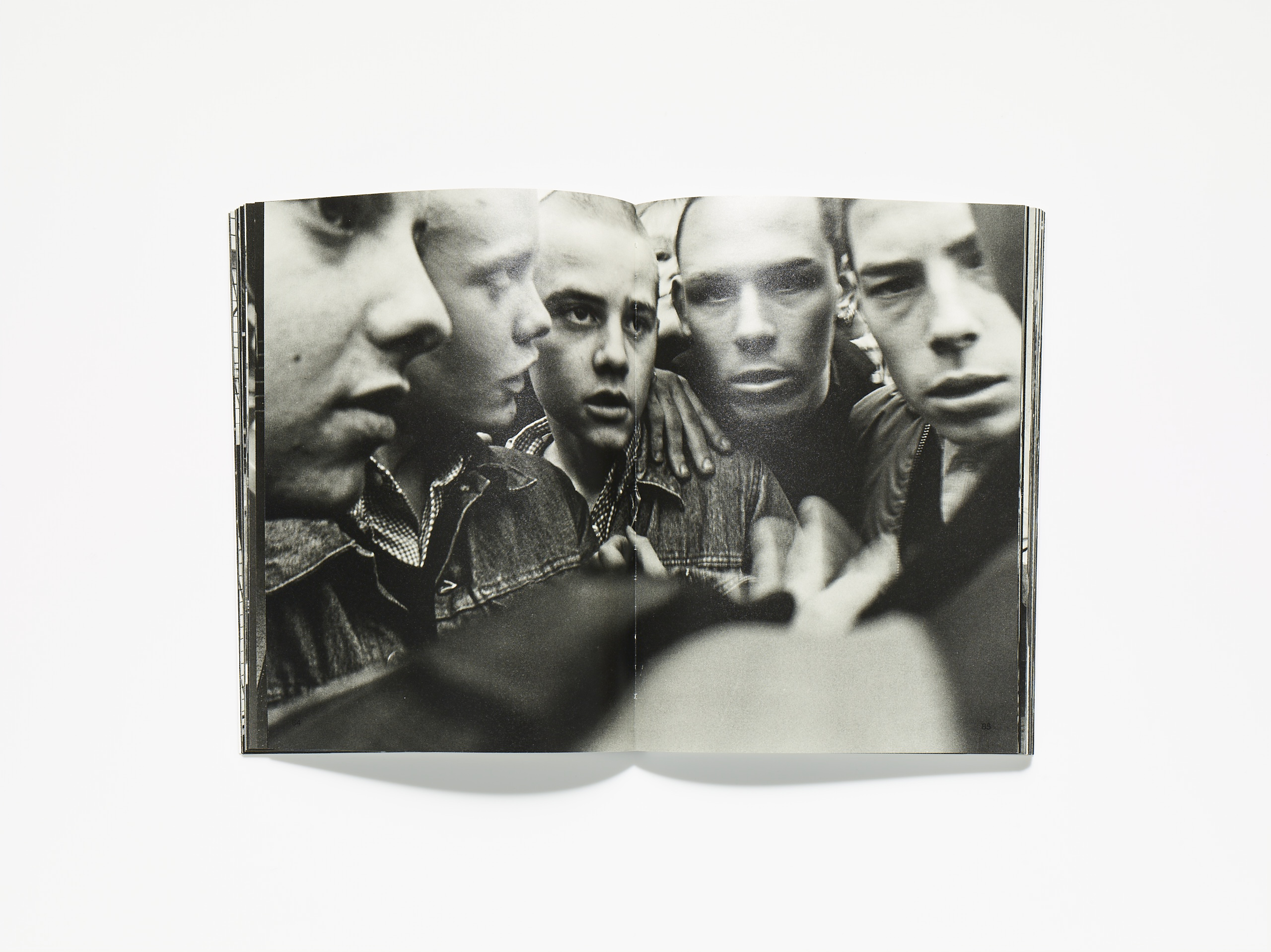

We Have No Place to Be: 1980-1982

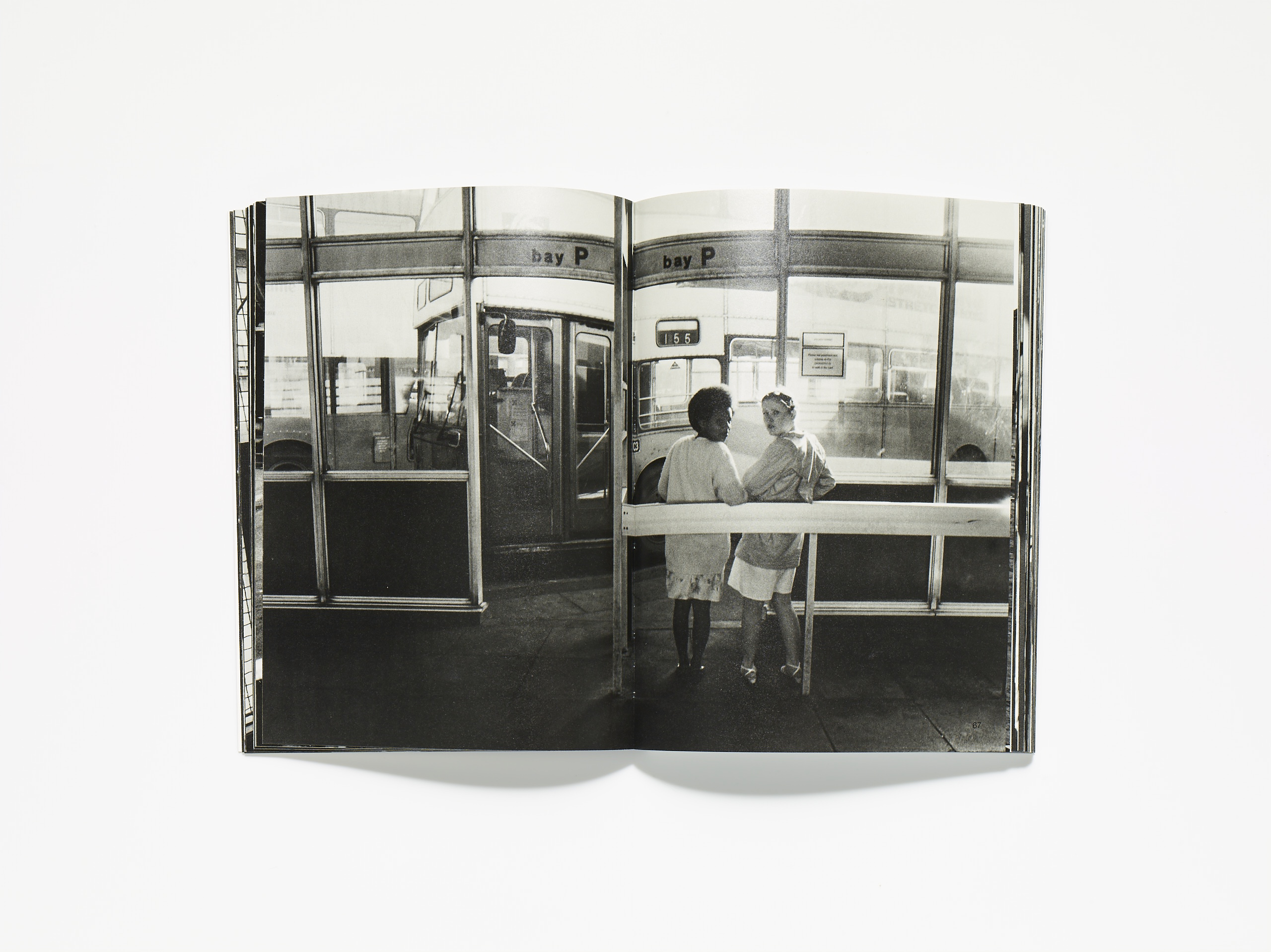

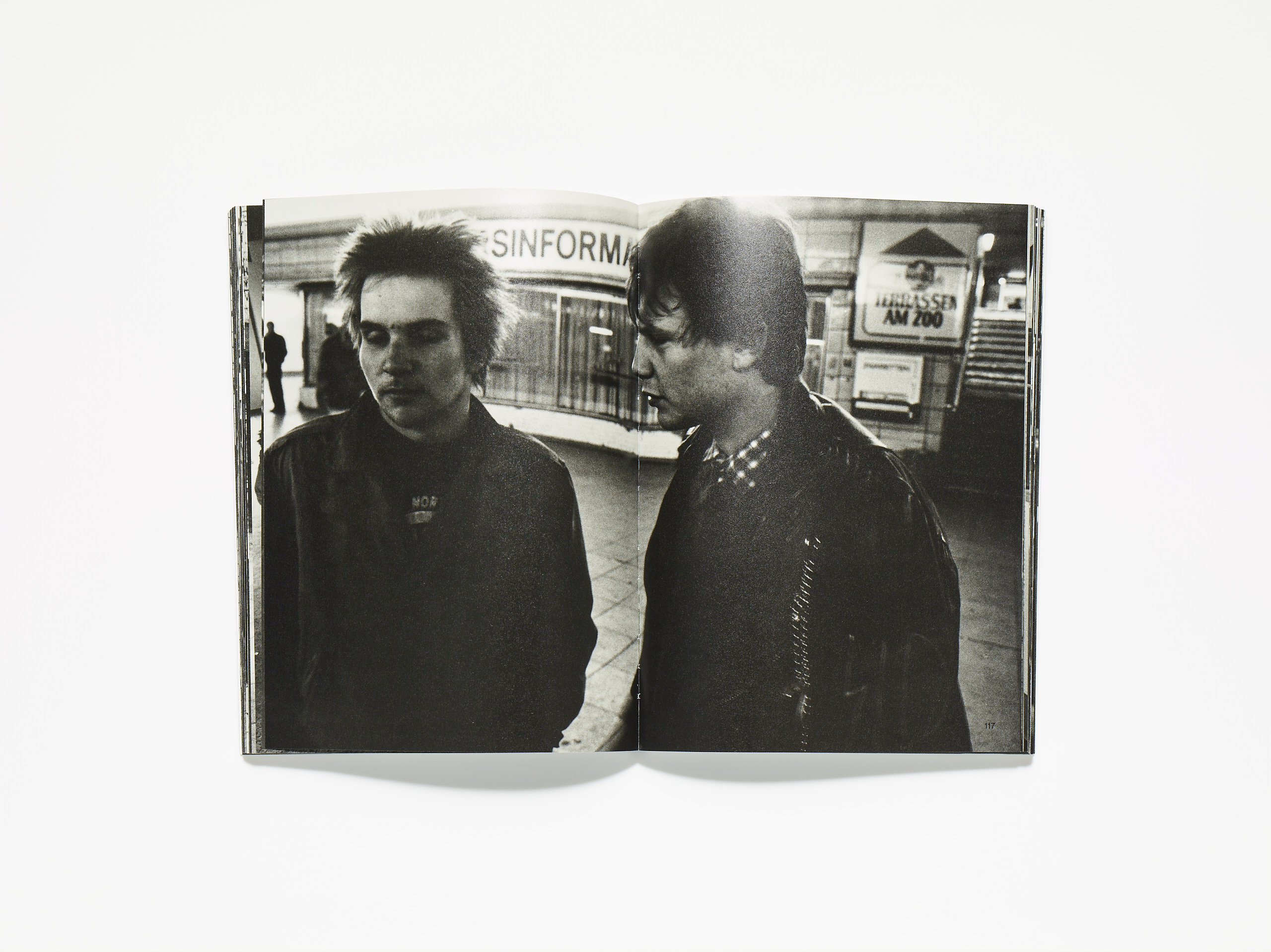

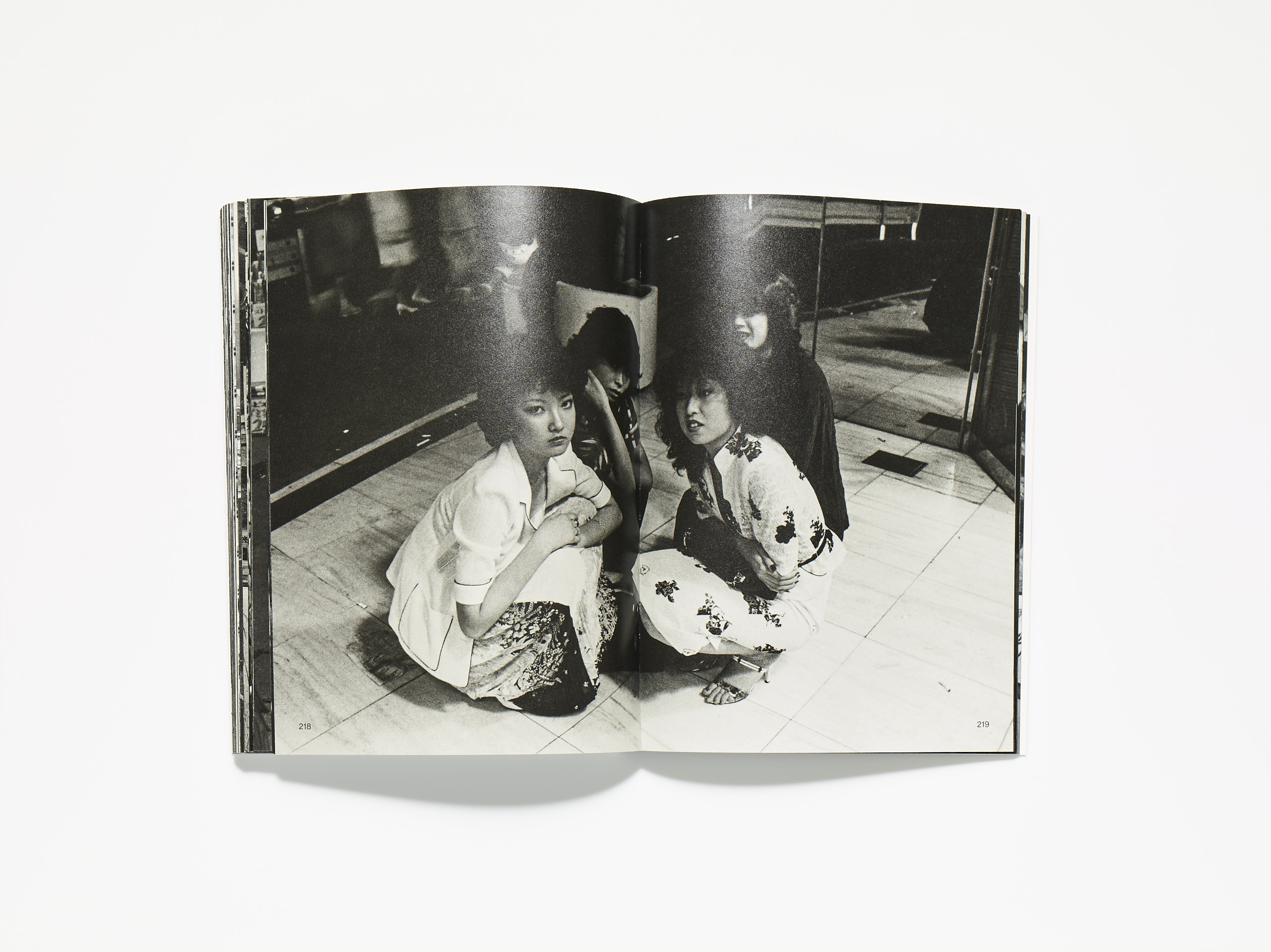

Liverpool, London, Nuremberg, West Berlin, New York and Tokyo

Session Press is pleased to announce the release of its eleventh publication, ”We Have No Place to Be: 1980-1982,” by renowned Japanese photographer Joji Hashiguchi.

Available here in a newly edited and expanded edition, We Have No Place to Be (originally published by Soshisha in 1982) veritably launched Hashiguchi’s illustrious 40-year career, and remains widely regarded as one of the photographer’s seminal early works alongside his first photobook Shisen ( The Look, recipient of the 18th Taiyo Prize in 1981). Supervised and edited by Hashiguchi himself, this omnibus edition comprises 139 black and white photographs, including more than 30 previously unpublished images. Printed in duotone with a matte finish, ”We Have No Place to Be: 1980-1982” provides a visceral window back into the eminently topical world featured within its 256 pages.

As society careened on a precipitous tilt, a generation of displaced youths fled their homes and schools, seeking refuge on the streets. Theirs was not only a flight, but a veritable fight against the stifling framework of an increasingly prescriptive life. In the early 1980s, Joji Hashiguchi similarly took to the streets of Tokyo armed with a camera, and began documenting these young compatriots in his debut work, Shisen. Before long, Hashiguchi would himself take flight – the Tokyo streets a runway for a larger world that beckoned outside Japan.

Recalling long high school nights spent listening to the Beatles, Hashiguchi first landed on the streets of Liverpool and London. Having encountered Christiane F.’s sensational 1978 autobiography, Wir Kinder vom Bahnhof Zoo (We Children From Zoo Station), he made his way from England to West Germany, traveling through Nuremberg and West Berlin. A budding Beatnik, he forayed even further West, at last arriving in New York. Over the course of his journey through these five cities, he sought to depict each through the youths that populated their streets.

Through his lens, we encounter an America exhausted by the Vietnam War. England under Thatcher, mired in rising unemployment and economic doldrums. West Berlin, on the frontline of the Cold War. Japan, erecting the scaffolding of her now labyrinthine bureaucratic society. Nearly four decades out, Hashiguchi’s We Have No Place to Be: 1980-1982 challenges present-day viewers to reexamine what we have both become and lost.

The complexities of youth have served as a captivating theme throughout the annals of photographic history. Photographers such as Danny Lyon, Karlheinz Weinberger, Bruce Davidson, Larry Clark, Nan Goldin, and Joseph Szabo made masterpieces with their investigations into the subcultures of renegade bikers, street gangs, and rebellious adolescents teetering on the dramatic cusp of adulthood. Similarly, photographers such as William Klein and Ed van der Elsken have produced distinctive street photos, famously snapped across the world’s metropolises in the 1950s and ‘60s. However, Hashiguchi is distinguished by a uniquely unwavering dedication to this theme. The sheer breadth of his travels in Tokyo and the West alike, coupled with a rapt intensity for documenting the “troubled youth” of the 1980s, culminated in a valuable document of an era.

Above all, Hashiguchi’s photos evince a preternatural ability to capture street youths in an unmediated, unguarded, intimate state. Eschewing a forced approach, Hashiguchi seemingly earned ready acceptance into the communities he photographed. Far from the clinical observer shining a floodlight on the city’s scars, Hashiguchi was understood by his subjects to be a sympathetic eye in their flailing struggle against authority and the contradictory injustices of society. As Hashiguchi reminisces, “I suspect their willingness to be photographed was in large part due to the simple fact that I was Asian.”

Since its initial publication in 1982, We Have No Place to Be has influenced generations of artists and photographers in Japan. One such artist and close friend is none other than Yoshitomo Nara, who has contributed a glowing essay reflecting upon Hashiguchi’s influence on his work, and a sage message for the present generation informed by his own experiences as a “lost” youth of the ‘80s.

We hope the present publication of We Have No Place to Be: 1980-1982 brings to a new international audience a work of profound historical and cultural importance destined to become a contemporary classic.

橋口譲二

『俺たち、どこにもいられない 1980-1982』

リバプール、ロンドン、ニュルンベルク、西ベルリン、ニューヨーク、東京

プレス・リリース セッションプレスの第11冊目の写真集は、橋口譲二の『俺たち、どこにも いられない 1980-1982』です。橋口のデビュー作として注目を集めた 『視線』1981年, 第18回太陽賞を受賞)と並び、『俺たち、どこにもい られない 荒れる世界の十代』(草思社 1982) は、写真家橋口譲二の40 年以上に及ぶ礎を築いた重要な初期作品です。30点以上の未発表の作品 を含めたモノクロ写真139点、256頁に及ぶ本書は、橋口自身が監修・ 編集し、2色刷りのマットニス加工印刷を施し、当時の街角や路上の空気を感じさ せる見応えある内容に仕上がっています。

社会が一つの方向に向かい始めた時、少年たちは家や学校を飛びだし路上にいました。規定された生き方かの枠から飛び出す。そのことは少年たちにとって「戦い」でした。 そんな東京の若者たちの姿を80年 代の初頭、『視線』を通し橋口は追求しました。その後、橋口の意識は東京の路上から日本の外に向かいます。

高校時代ビートルズを聞いていた橋口はリバプール、 ロンドンの路上に立つことから始めました。『われら動物園駅前の子どもたち』と題した一冊の本に触れた橋口はイギリスから西ドイツの街、ニュルンベルク、西ベルリンに移動します。その後、ビートニックに共感していた橋口はニューヨークに足を延ばしました。五つの都市を巡り、それぞれの都市の姿を、路上の少年たちを通して描くことに挑みました。

ベトナム戦争に疲弊し ていたアメリカ。サッチャー政権下で 不況と失業が深刻化していたイギリス。東西冷戦の最前に位置していた西ドイツ。管理社会が生まれ始めていた日本。本書『俺たちどこにも いられない 1980-1982』を通し、80年代 の若者たちの姿が、現代においてどのような意味を持つのかを改めて問い直し ます。

世界の写真史において、若者を主題にした作品は数多くあります。例えば、ダニー・ライアン、カール・ハインツ・ワインバーガー、ブルース・ デビットソン、ジョセフ・スターリンやジョセフ・ズザボは、バイク・ ライダーや、ストリート・ギャングなど路上に集まる若者の姿を捉えた 作品を残しています。また、巨匠ウイリアム・クラインや、エド・ファ ン・デア・エルスケンは、50年代から60年にかけて世界の主要都市を周 りストリートフォトを制作しました。しかし、東京のみならず欧米を周 り、80年代の「路上の若者」の姿に焦点を絞る作品は、日本写真史のみ ならず、世界においても数が少なく、本作は貴重な写真集と言えるで しょう。

また、積極的にコミュニケーションをとらずとも、路上の彼らの心の鎧を解いた、ある がままの表情を引き出したことは、橋口作品の魅力だと言えるでしょ う。それは、社会の矛盾や権威に打ちのめされながらも、不器用に抗う 若者の姿をとらえた橋口の視線が、社会の問題提起をする傍観者ではな く、路上の彼らに、一人の人間として共感を感じレンズを向けた真摯な姿 勢のためであると理解できます。橋口は「彼らが写真を撮られることを受け入れてくれた背景には、自分がアジア人だったことも大きい・・」とも語っています。

オリジナル版『俺たち、どこにもいられない 荒れる世界の十代』は、 82年に出版後、次世代の写真家、アーティストたちに多大なる影響力を 与えてきました。本書の序文において、美術家・画家の奈良美智が、作品から授かった インスピレーションや、自身の若い頃の体験に触れながら、暖かい言葉で今を生きる私たちに語りかけてくれています。『俺たち、どこにもいられない 1980-1982』を通し、多くの海外のコレクター、美術 関係者及び、日本の若い世代の作家に、橋口譲二の作品世界を改めて広 く紹介できることを願います。

Joji Hashiguchi

(Kagoshima, Japan, 1940)

Joji Hashiguchi was born in Kagoshima, Japan in 1940 and since he has received a award for the 18th Taiyo Prize for “Shisen” (”The Look” ) in 1981, he has published and exhibited his show domestically and internationally.

Publications:

“Hof Memories of Berlin” (Iwanami Shoten, 2011)

“Seventeen 2001-2006” (Iwanami Shoten, 2008)

“Children’s Time” (Shogakukan, 1999) “Freedom 1981-1989” (Kadokawa Shoten, 1998) “Dream” (MEDIA FACTORY, 1997)

“WORK 1991-1995” (MEDIA FACTORY, 1996)

“Couple” (Bungeishunju, 1992)

“BERLIN” (Ota Shuppan, 1992)

“Father” (Bungeishunju, 1990)

“Zoo” (Joho Center Shuppan kyoku, 1989)

“Seventeen’s Map” (Bungeishunju, 1988)

“We have no place to be” (Soshisha, 1982) and many others.

Exhibitions:

“Individual, Japan and Japanese” (Tokyo Polytechnic University Tokyo/Japan, 2017)

“BERLIN” “Couple”(Exhibition “Tokyo-Berlin” Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin/Germany, 2006) “WORK 1991-1995” (Japanische Kulturinstitut Köln Cologne / Germany, 2005)

“Couple” (“Japan Festival” Munich / Germany, 2000)

“WORK 1991-1995” (Traveling Exhibition supported by Japan Foundation New Delhi/India, Kuala Lumpur / Malaysia, Jakarta/Indonesia, London and various parts of England, 2000-2001)

“Couple” (“Internationale Fototage in Herten” Herten/ Germany, 1999)

“Couple” (Exhibition “Contemporary Japanese Photography”. Kunsthaus Zürich Zürich /Switzerland , 1993)

“Seventeen” (Instituto Giapponese di Cultura

Rome/Italy, 1990)

“Avoir 17 ans au Japon” (“Rencontres Internationales de la Photographie” Arles, Paris/France, 1989) and many more.

橋口 譲二

(1949年 鹿児島県生まれ)

1981年『視線』第18回太陽賞を受賞後、海外国内問わず、広く展示活動・出版を展開する。

主な出版物:

『Hof ベルリンの記憶』(岩波書店 2011年)、『十七歳 2001-2006』(岩波書店 2008年)、『子供たちの時間』(小学館 1999年)、『自由 1981-1989』(角川書店 1998年)、『夢』(メディアファクトリー 1997年)

『職 1991-1995 WORK』(メディアファクトリー 1996年)、『Couple』(文藝春秋 1992年) 、『BERLIN』(太田出版 1992年)、『Father』(文藝春秋 1990年)、『動物園』(情報センター出版局 1989年) 『十七歳の地図』(文藝春秋 1988年)、『俺たち、どこにもいられない』(草思社 1982年) 他、多数。

展示会:

『Individual 日本と日本人』(東京工芸大学 東京・日本 2017年)、『BERLIN』『Couple』(『東京ーベルリン展』ノイエ・ナショナルギャラリー ベルリン・ドイツ 2006年)、『職 1991-1995 WORK』(ケルン日本文化会館ケルン・ドイツ 2005年)、『Couple』(ミュンヘン日本祭り ミュンヘン・ドイツ 2000年)、『職 1991-1995 WORK』(巡回展 後援: 国際交流基金 ニューデリー・インド、クアラルンプール・マレーシア、ジャカルタ・インドネシア、ロンドン・イギリス各都市 2000-2001年)、『Couple』(ヘルテン国際写真フェスティバル ヘルテン・ドイツ 1999年)、『Couple』(『現代日本写真家展』クンストハウス・チューリヒ チューリヒ・スイス 1993年)、『十七歳』(ローマ日本文化会館 ローマ・イタリア 1990年) 、『十七歳』(アルル国際写真フェスティバル アルル、パリ・フランス 1989年) など多数開催する。