Miguel Calderón Interview

Miguel Calderón: Neurotics Anonymous

May 1 – June 7, 2025

Kurinanzutto

516 W 20th Street

New York

tel. +1 212 933 4470

newyork@kurimanzutto.com

tuesday to saturday: 10 am – 6 pm

Interview by James Maher

Japanese Translation by Miwa Susuda

JM: Can you tell us about the show?

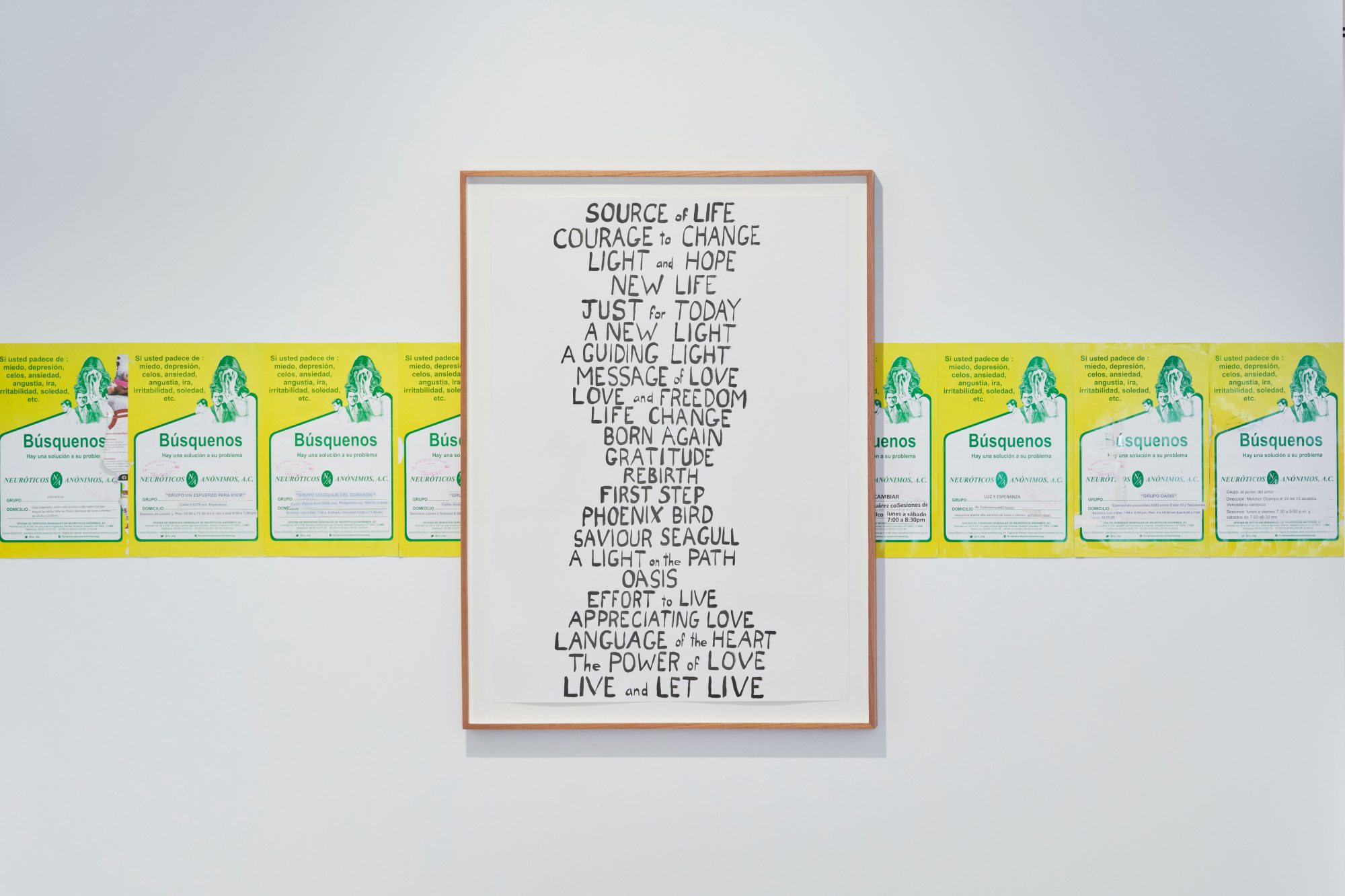

MC: Hi, I'm Miguel Calderon. Welcome to my show, Neurotics Anonymous. There's this spot in Mexico called Neurotics Anonymous, and I started following these posters that announced meetings. I started getting obsessed with the iconography that represents the association. And that's the beginning.

JM: Do you find yourself getting obsessed with ideas often?

MC: Oh, I am very obsessive. Definitely, very obsessive. It all started because I got obsessed with the iconography of this association called Neurotics Anonymous. I'm obsessed with psychology. I just started collecting these posters for the meetings and then I started attending the meetings. That was the starting point for the show.

JM: Was there a connection to your mother and your childhood?

MC: Yes, indeed. I grew up with a very neurotic mom, and this led to her actually going to some of these meetings. Not exactly Neurotics Anonymous, but a similar association.

JM: Can you tell us about the print behind you, it’s about your father?

MC: My father was a professional car racer, and when I was growing up, he got into a lot of accidents. There's a specific photograph where he pleads and says he will never race again after this accident. The photo was of an accident, and through my dad, I met a photographer that I really liked. I loved his work. They nicknamed him "The Vulture" in Spanish, and he was obsessed with documenting accidents. That's why they called him The Vulture—he was always waiting for accidents to happen. I remember my dad taking me to see his archive, and I saw this photograph of an accident, and it stuck in my mind. What really drew my attention more than the accident was that there was a photographer in the picture taking a photograph of the accident. So this photograph is a recreation of that image from memory. It was a black and white picture, so I recreated it. What really stuck in my mind wasn't the accident—it was our obsession with catastrophe, and more specifically, my obsession with catastrophe. I find myself continuously documenting situations that are catastrophic, like landscapes in disarray, and I think it just helps. It helps me get grounded and realize how all this catastrophe makes us very vulnerable and fragile. But at the same time, it makes me embrace my surroundings and live to the fullest.

JM: Was there trauma in a way, having a father as a race car driver?

MC: The more traumatic thing was when I was a young teenager, I tried to do go-kart racing. My dad wanted me to race. And the realization that I wasn't talented enough to be a car racer was kind of shocking. But I think all these elements have taken me to make art. What I enjoy about making art is that I choose one subject and become very obsessed with it, and I engage in very deep investigations.

JM: Can you tell us about Cocktail Hunters (Cocteleitors) and how you got involved with them?

MC: Yes, of course. I grew up going to art openings. I've always been a fan of art and I've always made art. I never decided I was going to be an artist—it's just something I always knew I was going to do. As a young teenager, I used to go to these openings because they offered free cheese, wine, and grapes mostly. There were violinists. It was very associated with classical art. But I remember the openings always had food, and I was one of the people that actually did see the art. But I've always seen people that just go and eat. I've done it also. More recently, I always explore what's close to me, what's really in my surroundings. I go to a lot of openings. I started noticing how a group of people went into the opening with empty backpacks, and then I noticed at the door that the backpacks were full. So I was very curious about this phenomenon.

I started talking to them and befriending them, and I realized that these guys, the Cocteleitors, live from eating food at openings. And it really drew my attention because it talks a lot about the dynamics and politics of art. They often talk about VIPs and exclusivity, and I've always been very against exclusivity. So yeah, as with all my film projects, if I don't attain close proximity to the people I'm filming, it doesn't work. So we've actually become friends. And, you know, you often judge people. You see them eating at an opening and you tend to judge. In this case, I wanted to explore where they were coming from with more empathy. In this video we explore their backgrounds. It's 30 minutes, but it's part of a longer project. It's ongoing. So I'm going to continue exploring the subject.

JM: Can you tell me a little bit about the man in that other 4x5 print?

MC: Yes, that's Luis, one of the Cocteleitors as they call themselves. And we've become quite close. We write each other. And him specifically, I was drawn to the way he dressed. He dressed like 70s rock and roll. I've always had this fixation with his style. Then I found he was part of this group. They have a chat in which they send each other events where there's food. Different groups. Sometimes they don't want others to find out so they can eat the best food available. Luis is a super kind, loving guy. Just following him around—his look is so imposing, and I really wanted to do a portrait of his. So I got a 4x5 camera and we did this very straightforward portrait at a friend's house. And as in a lot of my work, especially photography, I feel like once I see the photograph—they're always negatives, 35mm and 4x5s—once I sit down and start scanning the images, I always find these revelations. And the moment I saw the image of Luis, I was shocked by how much he looked like Antonin Artaud.

Antonin Artaud was a French poet who spent a lot of time in Mexico. He went to visit and study in the north of Mexico and studied the effects of peyote. So I titled that photograph The Reincarnation of Artaud, because I felt that the picture captured the spirit of this poet that I really admire.

JM: They are very profound in the video. They're very sensitive.

MC: It's become very interesting to me how they are critics. We go to openings and tend to have very similar opinions. I engage in very deep conversations about the art world in Mexico, how it was in the 80s and how it's changed in the 90s. They used to offer food for the press—they don't anymore. They wanted to draw in people, so they had to adapt. I often engage in very interesting conversations, and they're very critical of the work. Many times we share the same opinions. I really like that because they're very straightforward. If they don't like something, they say it's a piece of shit. And often, I feel the same way. So it's nice to hear their unfiltered opinions. And yeah, they probably see more art than anybody. They pretend to take pictures at the openings just to get to the drinks. But as you see in the video, one of them talks about how he loves Van Gogh. And it is very profound. It shows how art connects to people on different levels.

JM: You started a collective in Mexico City. Can you tell me about that?

MC: Of course. In the early 90s, me and a group of young artists started an art space called La Panadería, which was an old bakery. Basically, we were tired of protocols and having to kiss people's ass to get a show. So we just did it hands on—do it yourself. Actually, that's the title of Social Thing, about how I despise social climbing. It’s a little bit literal, and I know it means many other things, but that’s the spirit.

JM: When you were younger and into art, did you want to be a filmmaker or do a mix of things?

MC: I had this presentation with teenagers the other day, and it was very profound. They asked me, what's your favorite art form in your work? My visceral answer was: making films. I really love embracing the moments that surround me and taking them to the limit.

But when I'm done with a film, the amount of people you work with is overwhelming. So I need my own space. I start drawing—very personal, very quiet, meditative ink drawings that I start spontaneously. When that gets tiring, I go out and take photographs.

I don't have a favorite medium, but I find a home for different things in each one. I do like classic photography. My photographs are very straightforward. I don't use Photoshop. I do some color correction, but they're very raw. I shoot most of them with point-and-shoot cameras, other than the 4x5s. It's a straightforward exercise in trying to see things others don't—or even I don't, until I start scanning the negatives. That's what surprises and shocks me in a positive way about photography.

JM: Between the power of a single print and a whole movie, how do they compare for you?

MC: Yeah. I often say that if I could, I would just make films, but it's completely contradictory. I know it's not true. I'm lying to myself. Because every time I finish a film, I want to regroup, and I start taking photographs and making drawings. I'm very lucky that I'm addicted to making art. It's my addiction.

JM: Did you have ADHD growing up?

MC: Yeah, I definitely had ADHD growing up, but I find it absurd. I think it's an excuse to medicate children. My ADHD showed up in physics and math class. But the moment I started studying art, it went away. Of course you're going to have ADHD if you don't like a subject—if it's boring or puts you to sleep. Actually, these drawings come from that time. During math and physics classes, I started making little drawings.

JM: Did you always draw when you were younger?

MC: I drew in my notebooks. I made a lot of grotesque and sarcastic cartoons about my teachers. They were so hard on me. It was a form of escape so I didn’t have to deal with the math and the physics. I failed constantly—which wasn’t good.

JM: How is the gallery scene in Mexico City compared to New York?

MC: The openings in Mexico are very vibrant. The interesting thing about the characters in the film is that they don't only go to art openings—they go to any event where there's food offered. I focus on the art events because that's the world I know. I try to make art about subjects that I know well.

ミゲル・カルデロン インタビュー

『神経症者匿名の会』

2025年5月1日〜6月7日

クリマンゾット

516 W 20丁目

ニューヨーク

電話:+1 212 933 4470

メール:newyork@kurimanzutto.com

営業時間:火曜〜土曜 午前10時〜午後6時

インタビュー:ジェームズ・メイハー

日本語翻訳:須々田美和

J: この展覧会について教えていただけますか?

M: こんにちは、ミゲル・カルデロンです。僕の展覧会「神経症者匿名の会」へようこそ。 メキシコに「神経症者匿名の会(Neurotics Anonymous)」という場所があって、そこの集会を告知するポスターを追いかけるうちに、そのアイコンやビジュアルに取り憑かれてしまいました。それがすべての始まりです。

J: よく何かに取り憑かれることはありますか?

M: ええ、とても強迫的なんです。本当に。 この展覧会の始まりは、「神経症者匿名の会」のアイコンに取り憑かれたことでした。僕は心理学に夢中で、その集会のポスターを集め始めたんです。それから実際に集会に参加するようになりました。そこからこの展覧会の構想が生まれました。

J: お母さまと子ども時代との関係はありましたか?

M: ええ、あります。僕はとても神経質な母のもとで育ちました。母もこうした集会に通っていたことがあるんです。正確には「神経症者匿名の会」ではありませんが、似たような会でした。

J: 後ろにあるプリントについて教えてください。お父さまに関係があるとか?

M:

父はプロのレーサーで、僕が子どものころ、よく事故を起こしていました。ある事故のあと、二度とレースはしないと誓った時の写真があります。その写真には、事故の現場が写っているのですが、父を通じて、事故ばかりを記録するフォトグラファーと出会いました。彼のあだ名は「ハゲタカ」でした。事故をひたすら追いかける姿から、そう呼ばれていたんです。

ある日、父に連れられてそのフォトグラファーのアーカイブを見に行ったとき、事故の写真の中に、その事故を撮影しているカメラマンの姿が写っていて、それが強烈に記憶に残りました。

この作品はその記憶をもとに再現したものです。元の写真はモノクロで、僕も白黒で再現しました。僕の心に残ったのは事故そのものではなく、「破滅への執着」でした。そしてそれは僕自身の執着でもあります。崩壊した風景など、破局的な状況を記録し続けることで、自分の存在を確認しているのかもしれません。破滅が私たちをどれほど脆くするかを知る一方で、その現実を受け入れ、今を精一杯生きる力にもなっている気がします。

J: レーサーの父親を持つことは、トラウマになりましたか?

M: よりトラウマだったのは、10代の頃に自分もカートレースをやってみたことです。父に勧められて始めたのですが、自分に才能がないと気づいたときはショックでした。でもその経験すべてが、今のアート制作につながっています。僕がアート制作で楽しんでいるのは、ひとつのテーマに深く取り憑かれて、徹底的に探求できることです。

J: 「カクテル・ハンターズ(Cocteleitors)」について、どう関わるようになったのですか?

M: 子どものころから、アートのオープニングにはよく行っていました。アートが大好きで、自分でも作っていました。でも「アーティストになろう」と決めたわけではなく、自然とそうなっていた感じです。

若い頃、アートのオープニングには無料のチーズやワイン、ぶどうがあって、バイオリン演奏まであるような、クラシックな雰囲気でした。でも僕は、ちゃんとアートも見ていた方でした。

最近もオープニングに頻繁に行くんですが、空のリュックを持って入って、帰る頃にはいっぱいになってる人たちがいることに気づいて、不思議に思って話しかけてみたんです。

彼らは「コクテレイトール」と呼ばれていて、オープニングの食事で生活している人たちでした。この現象に惹かれたのは、アート界の構造や排他性についての示唆があるからです。VIPや排他性を重視する文化に、僕はずっと反発してきたので。

このプロジェクトも他と同じで、被写体と近い関係を築かないと成立しません。実際に友だちになって、彼らの背景を30分の映像で記録しました。これはもっと長いプロジェクトの一部で、これからも続けていきます。

J: その隣の4x5プリントの男性についても教えてください。

M: 彼はルイス、コクテレイトールのメンバーの一人で、今ではとても親しい友人です。彼の70年代風のロックスタイルに惹かれて、ポートレートを撮りたいと思いました。4x5のカメラを使って、友人の家でストレートなポートレートを撮影しました。

僕の作品ではよくあるのですが、ネガ(35mmや4x5)をスキャンして初めて気づくことが多いです。彼の写真を見た瞬間、「アントナン・アルトーにそっくりだ」と驚きました。アルトーはフランスの詩人で、メキシコにも滞在し、ペヨーテの研究もしていました。

だからこの作品には「アルトーの転生」というタイトルをつけました。彼の精神性をとらえた写真だと感じたからです。

J: 映像の中で、彼らはとても繊細で批評的ですね。

M: そうなんです。彼らはアートに対して鋭い視点を持っていて、よく話が合うんです。80年代から90年代のメキシコのアート界の変化、メディア向けの食事提供の廃止など、深い話をよくします。彼らの意見は率直で、「これはクソだ」とはっきり言う。僕も同感のことが多くて、そういう正直な意見は貴重だと思います。彼らは誰よりも多くの展覧会を見ていると思います。

一見すると、飲み物をもらうために写真を撮るふりをしているだけかもしれませんが、あるメンバーはゴッホが大好きだと言っています。アートが人と深くつながっている証拠です。

J: メキシコシティで立ち上げたコレクティブについて教えてください。

M: もちろんです。90年代初頭に、若いアーティストたちと一緒に「ラ・パナデリア(La Panadería)」というアートスペースを立ち上げました。元はパン屋だった場所です。展覧会をやるには、いろんな人に媚びを売らないといけない状況にうんざりして、自分たちで始めたんです。 この「ソーシャル・シング」というプロジェクト名も、社会的地位を得ようとする行為に対する嫌悪感から来ています。文字通りの意味もありますが、僕の精神をよく表しています。

J: 若い頃、映画を作りたかったですか?それとも色々な表現をやりたかった?

M: この前、10代の若者向けにプレゼンをしたんですが、「一番好きな表現は何か?」と聞かれて、直感的に「映画を作ること」と答えました。

でも映画を作り終えると、関わる人数の多さに圧倒されて、自分の時間が欲しくなります。だから静かにドローイングを描き始めたり、外に出て写真を撮ったりします。僕には決まった表現媒体はなくて、それぞれの表現に「居場所」があるような感覚です。

写真はとてもストレートです。Photoshopは使いません。色補正はしますが、基本的にとても素朴な手法です。ほとんどがコンパクトカメラで撮影しています(4x5以外)。ネガをスキャンして初めて気づくことが多く、そこに写真の驚きと喜びがあります。

写真1枚の力と映画1本の力、どちらがより強いと感じますか?

もし可能なら、ずっと映画だけを作っていたいと思うこともあります。でもそれは嘘なんです。映画が終わると、また写真やドローイングに戻りたくなる。

僕は「アートを作ること」に中毒なんです。とても幸運なことだと思います。

J: 子どもの頃にADHDがありましたか?

M: ええ、確実にADHDでした。でも、それは子どもに薬を与えるための口実のように感じています。僕のADHDは物理や数学の授業にだけ現れていました。でもアートを学び始めた途端、なくなったんです。興味のないことに集中できないのは当然ですよね。

実際、今のドローイングの原点はその頃にあります。物理や数学の授業中に、落書きをしていたんです。

J: 小さい頃からずっと絵を描いていましたか?

M: ノートにたくさん描いていました。教師たちを風刺した、グロテスクで皮肉な漫画ばかりでした。先生たちがとても厳しかったので、それが逃げ道だったんです。数学と物理はずっと落第でした。もちろん、良いことではなかったですが。

J: メキシコシティのギャラリーシーンは、ニューヨークと比べてどうですか?

M: メキシコのオープニングはとても活気があります。映画に登場する人々は、アートのオープニングだけでなく、食事が出るあらゆるイベントに行くんです。 僕は自分がよく知る世界について作品を作るようにしています。その意味で、アートのイベントを中心に扱っています。