Stacy Kranitz and Chris Verene

”The Safety Net”

Psychic Readings: 629 E 6th St New York, NY 10009

Exhibition Date: April 3 - May 10, 2025

Gallery Hours: Wed - Sat 12 - 6 pm and by appointment

Curated by Ani Cordero

Interview by James Maher

Japanese translation by Miwa Susuda

James: Okay, we need some sort of good starter, if you could tell us a little bit about the work you’re showing and how it came together.

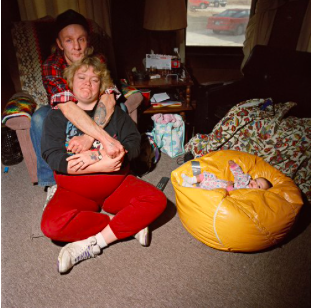

Chris: I’m Chris Verene. I’m here with my friend, Stacy Kranitz. We’re both documentary photographers, and we’ve been photographing in America for a lot of years. We have a show—it’s kind of a retrospective—looking back over our pictures, my pictures from Illinois and Stacy’s pictures from Appalachia, spanning a long time.

The idea for the show is to focus on the safety net. Many people in both of our sets of work are supported by the safety net: Social Security, the hospital system, emergency rooms, harm reduction centers, food stamps, emergency heating bill coverage, Women, Infants, and Children (WIC)—things like baby formula. A lot of this support comes from federal and state governments. When people are in real trouble, those programs can be the only thing keeping them alive—like housing subsidies for people with disabilities. Much of that is present in this show, which looks back over some 30 years of pictures. So welcome, and hello.

Stacey: That was really moving. We should talk about the curator, Ani.

Chris: We’re joined in this show by the curator, Ani Cordero. Ani is a Puerto Rican activist with a background in political science who has worked for many years on the island in Puerto Rico. After the hurricanes, she started a charity with another Latin indie artist, to try to get direct grassroots support to people. Even though there’s a safety net, in a situation like Hurricane Maria, sometimes that net doesn’t help or may not work—it’s too hard to maintain. The curation Ani is doing involves looking at our pictures through the perspective of, “If these people needed help, how would that work? What would that look like?” There’s this in-between idea where you’re with them, but also outside of them, thinking about them as a historical class of people who may need our support. Ani’s charity on the island was about getting direct help to people. In a way, photographers who show up and do stories about people in need are also engaging in a kind of direct action. Stacy does a lot of work that gets published very quickly: you make it, then it’s out there. So there’s a powerful sense that the photos we make can face the world soon after they happen.

James: Both of your works have a similar spirit, yet Chris, you were photographing your home—and Stacy, you were coming into a new community, one that has a fraught history with photography, and it's clear how aware you were of that history. How did you both feel about this issue? Were you nervous about how you characterized these communities, and about doing them justice?

Stacy: Yeah. Well, first I would say that when I was starting out, Chris was one of the first photographers who really inspired me. What struck me in his work, which was on display at a gallery when I first came to New York ages ago, was this sense of play and humor, but also serious care. Once I understood that these were his family members and that he had spent so much time developing relationships with them through the camera, it made sense. I work differently—I do have some long-term relationships, but I also encounter people as a stranger on the street.

I always think that we want to believe photographs “capture” a place, as though the photograph is the truth. Deep down we know that’s not really the case. So I’m very careful to say these photographs do not essentialize a place or a people—that’s not what they’re about. They’re catalysts for conversation. That’s what the photographs mean to me.

Chris: That’s interesting. I haven’t heard you phrase your philosophy exactly like that, but it’s true: we’re showing our truth, but also trying to reflect our subjects’ truths. An audience member who sees these images—depending on how informed they are—will have different understandings of what’s really happening. I try to make pictures that can become deeper if you spend the time to learn more about the situations. It’s interesting because the documentary style we both use can vary. I don’t necessarily stop people on the street because I already know a lot of people, but you could stop someone on the street and make an amazing picture. Both approaches are valid. Depth can happen in an instant, but it also remains open to interpretation.

Stacy: I always think of it as a triangle—there’s the photographer, the subject, and the viewer, and we’re all in conversation with each other. I really feel that in this show, and it’s a privilege to have my work next to yours.

Chris: And we have the same publisher, Twin Palms. Jack Woody, who started Twin Palms, used to say he wanted to publish books that other people wouldn’t do—often subject matter that needs attention. They have a lot of books people need to be talking about, most of it is documentary or transgressive in some way. I love being part of that.

I really like your triangle metaphor, especially when the middle of the triangle is truth. All three points—photographer, subject, and viewer—are usually looking for what’s really going on. People in New York might look at these photos of Appalachia or Illinois and think it’s far away, but really, it could be just around the corner from here. People want to know what’s happening in the world. I’m always searching for a more complete truth. That’s why I keep taking pictures—I’m trying to tell a bigger, broader story. We’re both personal artists, like you said. The space in the middle of that triangle is multiple truths, right?

Stacy: Yes, multiple truths. And during such a divided time, I think it’s really important for us to come together by allowing for multiple truths.

James: Stacy, I really enjoyed how you brought your research and personal experience into the show, into your work, and into your book. Can you talk about that process again?

Stacy: For this show, Chris and I wanted to do something playful and fresh. For me, in the time after the election, I spent a lot of time in my studio working through my feelings, playing with scraps, glue, and watercolor, and reckoning with my archive—these materials in my studio. I wanted to share them in an informal way, as an experiment. Of course, they all relate to the idea of the safety net and mutual aid, which is another thing we thought about when developing this show. When the safety net fails, there’s this beautiful history of mutual aid, and I think that’s going to be increasingly important.

James: Is there anything about Appalachia or Illinois that you want to tell people watching this—something about those places, or anything you feel is important right now?

Stacy: Sure. I always remind people that Appalachia is a huge region. It’s actually a government-constructed concept—something like 260 counties across 13 states. We’re talking about a big chunk of America, and a lot of people have connections to it. It’s a deeply rich place that’s suffered from extraction. That’s something we need to think about now with environmental regulations rolling back. This is a place with a history of exploitation, and it’s important to slow down and realize how many layers of history and life there are. Multiple truths matter.

I also included a series—pamphlets for the healthcare system. I wanted to develop some sort of gesture. I wrote some grants to do five different issues, obviously relevant anywhere, but especially relevant here.

James: How does that connect post-election? Do you see your community getting hit harder already?

Stacy: I think we’re just starting to see it now. Sometimes you want to know exactly what’s going to happen, but we have to wait until they announce these very harsh penalties and cutbacks.

Chris: Yes—I encourage you all out there to talk to your neighbors and get to know them. When you travel, talk to people. This is a great time to do that. Not everyone is that gregarious, but I encourage you to build community in your life and look for new ways to do it, even when you’re uncomfortable. Knowing neighbors and talking to strangers can help when we need mutual aid or when things are tough. Building community can help you; maybe it helps to look at photography about what’s going on in the world. But definitely, we need each other. It’s so hard for everyone right now. We know more is coming, and we just have to wake up every day.

ステイシー・クラニッツ & クリス・ヴェリーン

「セーフティネット」

会場:Psychic Readings(629 E 6th St, New York, NY 10009)

展示会期間:4月3日ー5月10日

営業時間:水曜~土曜 12:00~18:00(予約制でもご覧いただけます)

キュレーション:アニ・コルデロ

インタビュー:ジェームズ・マハー

日本語翻訳:須々田美和

ジェームズ:じゃあ、最初に、お二人が今回展示している作品について聞かせてください。どんな内容で展示の開催となったかも教えてもらえますか?

クリス:はい、もちろんです。僕はクリス・ヴェリーンといいます。今日は友人のステイシー・クラニッツと一緒に来ました。僕たちは二人ともドキュメンタリー写真家で、アメリカ各地を長い間撮ってきました。今回の展示は、ある意味で僕たちにとって回顧展のような形になっていて、僕はイリノイ州で撮ってきた写真、ステイシーはアパラチア地方での作品を紹介しています。テーマになっているのは「セーフティネット(社会的な安全網)」です。僕たちの写真に登場する多くの人たちは、社会保障や医療、救急、ハームリダクションセンター、フードスタンプ、暖房費の補助、そしてWIC(女性・乳児・子ども向けの支援)など、連邦政府や州から提供された制度に支えられて生活しています。そして、本当に困っているときには、そうした制度だけが命をつないでくれることもあります。障がいのある人たちへの住宅補助なんかもそうですね。そういった支援を受けている人々の暮らしの様子を、30年にわたって撮影してきた写真を今回の展示を通して振り返るものになっています。

ステイシー:あと、この展示のキュレーター、アニについても紹介したいな。

クリス:うん、今回の展示では、アニ・コルデロがキュレーターとして関わってくれています。アニはプエルトリコ出身の活動家で、政治学のバックグラウンドもあって、長年プエルトリコで様々な社会運動に取り組んできた人です。ハリケーンのあと、ラテン系のインディーミュージシャンの仲間と一緒に、現地の人々に直接支援を届けるための団体を立ち上げました。 セーフティネットがあっても、たとえばハリケーン・マリアのような大きな災害が起きたときには、制度が機能しなかったり、維持できなかったりすることがありますよね。アニのキュレーションでは、「この写真の中の人たちが支援を必要としているとしたら、それはどう機能するのか?どう見えるのか?」という視点で作品を見ることを促します。彼女は、被写体に寄り添いながらも、歴史的な文脈の中で支援が必要な人々を捉えようとする、ちょっと俯瞰した視点も持っているんです。アニがやっていた支援活動は、まさに人々に“直接手を差し伸べる”というものでした。実は僕たち写真家も、ある意味でアニと同じように「直接的な行動」をしているのかもしれません。特にステイシーの作品は、撮ったらすぐ発表されることが多いので、写真ができてすぐに世の中に問いかけることができるんです。

ジェームズ:お二人の作品の間には通じるものがあると思います。クリスさんは自分の故郷を撮っていていますが、一方でステイシーさんはまったく新しいコミュニティに入っていったわけですよね。特にアパラチアは、写真に対して複雑な歴史を持つ地域でもあります。そのことをきちんと意識して作品づくりをされているのが伝わってきます。この点について、どう感じていましたか?コミュニティの捉え方や、それをどう伝えるかについて、不安はありましたか?

ステイシー:そうですね…。まず最初に言いたいのは、私が写真を始めた頃に、クリスの作品にものすごく影響を受けたんです。ニューヨークに出てきたばかりの頃、ギャラリーで彼の写真を見て、「あっ、こういう視点で人を撮ることができるんだ」って衝撃を受けました。クリスの作品は、遊び心やユーモア、でも同時にすごく深い思いやりがあった。あとで、写っているのが彼の家族で、長い時間をかけて関係性を築いてきたということを知って、すごく納得がいったんです。私のアプローチは少し違っていて、もちろん長期で付き合う人もいますけど、街中で出会った人を撮ることも多いんです。完全に見知らぬ人とのやりとりから始まることも多いので、毎回が新しい出会いなんですよね。よく「写真はその場を“切り取る”もの」と言われますけど、実際には写真がその土地や人々の“真実”を完全に表すものではないって、私たちも本当はわかってると思うんです。だから私は、これは「ある場所や人々を代表する写真」ではなくて、「会話のきっかけになる写真」なんだと、いつも意識しています。私にとって、写真はそういう存在なんです。

クリス:すごく興味深いなあ。ステイシーがそういうふうに言葉にしてるのを初めて聞いたけど、本当にその通りだと思うよ。僕たちって、自分たちの“真実”を見せると同時に、被写体の“真実”をどう伝えるかっていうバランスも大事にしてるよね。観る人がどれだけその背景を知っているかによって、同じ写真でも受け取り方は全然違ってくるし。 僕はね、時間をかけて見れば見るほど、もっと深いところまで届くような写真を撮りたいと思っているんです。だから、簡単には「わかった気」になれないような、でもちゃんと向き合えば何か伝わる、そんな写真が理想なんですよ。僕たちがやっているドキュメンタリーのスタイルって、ほんとに幅があると思う。僕は通りで知らない人に声をかけて撮ることはあまりしないけど、ステイシーみたいに、それで素晴らしい写真が生まれることもある。どっちが正しいとかじゃなくて、どちらのやり方もちゃんと意味があるんだと思う。写真の深さって、偶然の一瞬にもあるし、長い時間の中にもあるよね。どの様に人に解釈されるかっていうのを作家としてオープンにすることも大事だと思うよ。

ステイシー:私ね、写真を考えるときにいつも「三角形」のイメージを持っているの。写真家、被写体、そして観る人。その三者がずっと対話し続けているって感じ。今回の展示でも、それがすごく強く感じられるの。クリスの作品の隣に自分の作品が並んでいることを、本当に光栄に思っています。

クリス:うん、僕たち同じ出版社、Twin Palmsから本を出してるんだよね。Twin Palmsを立ち上げたジャック・ウッディって、よく「他の出版社がやらないような本を出したい」って言ってたんです。世の中であまり語られないようなテーマや、人々がもっと向き合うべき現実を扱った本が多くて、その多くがドキュメンタリーだったり、ちょっと挑戦的な内容だったりするんですよ。Twin Palmsからの写真家の一員でいられること、本当に嬉しいなって思ってます。ステイシーの「三角形」っていうメタファー、僕もすごく好き。しかも、その真ん中にあるのが“真実”だっていうのがいいよね。写真家と被写体と観客、三者ともが「本当は何が起きているのか」を探ろうとしている。ニューヨークにいる人が、アパラチアやイリノイの写真を見たときに「遠い世界の話」って思うかもしれない。でも、実際にはそれってこのすぐ隣で起きてることかもしれない。みんな、世界で何が起きてるのか知りたいんですよね。僕もいつも、もっと広い、もっと深い「真実」を探し続けてる。それが、写真を撮り続けてる理由の一つでもあります。さっきステイシーが言ってくれたみたいに、僕たちはとても“個人的な”作家なんだと思う。そしてその三角形の真ん中にあるのは、「ひとつじゃない、多様な真実」なんだよね。

ステイシー:そう、まさに「多様な真実」。今みたいに分断が進んでいる時代だからこそ、お互いの違う真実を認め合うことが、私たちがまたつながっていくために本当に大事だと思うんです。

ジェームズ:ステイシーさん、今回の展示や作品、そしてご自身の本にも、リサーチや個人的な体験がすごく反映されていると感じました。そのプロセスについて、もう少し詳しくお話しいただけますか?

ステイシー:はい。今回はクリスと一緒に、ちょっと遊び心のある、いつもと違う新鮮なアプローチをやってみたいと思っていたんです。私は、選挙の後にかなり混乱していた時期があって、スタジオでひとり、自分の気持ちを整理するように制作をしていました。手元にあった紙の切れ端を使ったり、糊を貼ったり、水彩を塗ったり…。そうやって、自分のアーカイブに向き合う時間が増えたんです。今回は、そうした素材をあえてカジュアルに、ちょっと実験的なかたちで見せてみたいと思いました。でも根底にはやっぱり「セーフティネット」や「相互扶助」のテーマがありました。私たちも展示の準備をしながら、「もしこの社会的な支援が機能しなくなったら、私たちはどう助け合うんだろう?」ということをずっと考えていたんです。支援制度が機能しないとき、人と人とが直接支え合う「相互扶助」の歴史って、すごく素晴らしいと思うし、これからますます大事になってくる気がしています。

ジェームズ:アパラチアやイリノイについて、展示を見ている人たちに伝えたいことってありますか?今のタイミングだからこそ、話しておきたいことがあればぜひ。

ステイシー:はい、もちろんです。私はいつも「アパラチアって、すごく広い地域なんです」と説明するようにしてるんです。実は、アパラチアってアメリカ政府が定義したエリアで、13の州にまたがる260以上の町が含まれているんですよ。つまり、すごく多様で、広大なアメリカの一部なんです。そして多くの人が、実は何らかのかたちでこの地域とつながりを持っている。だから、どこか“遠くて特別な場所”というよりは、もっと身近な場所なんだと思っています。でも、この地域は長い間、資源の搾取や労働の問題で苦しんできた歴史があります。今、環境規制がどんどん緩められている状況を見ると、その歴史がまた繰り返されるかもしれないという不安もあるんです。だから、私たちがこの土地をどう見るか、どう関わっていくかを、もう一度ちゃんと考えるタイミングなんじゃないかなって思います。それから、今回の展示では医療制度に関するパンフレットもシリーズで展示しています。私にとって、何かしらの「行動」を示したかったんです。それで、自分で助成金を申請して、5種類のパンフレットを作りました。内容としては、もちろんどこででも通用する話なんですが、特にこの地域で、今の時代にこそ必要だと感じたんです。

ジェームズ:それって、選挙後の状況とも関係しているのでしょうか?すでにコミュニティに影響が出始めている実感はありますか?

ステイシー:そうですね、まさに今、少しずつその影響が出始めているところだと思います。正直、何が起こるのかはまだ分からない。でも、これから発表されるであろう厳しい予算削減や制裁のことを考えると、覚悟しておかないといけないなって思っています。

クリス:本当にその通りだと思います。だから、皆さんにもお願いしたいんです。ぜひ、近所の人と話してみてください。旅に出たときも、できるだけ現地の人と話すようにしてみてほしい。みんなが社交的ってわけじゃないけど、少しでもいいから、自分の暮らしの中で「コミュニティをつくる」ということを意識してほしいんです。不安なときや困ったとき、助けになるのはやっぱり人とのつながりだと思うんですよ。

たとえば、写真を通して「今、世界で何が起きているのか」を知ることも、そうしたつながりのひとつかもしれません。今は誰にとっても厳しい時代だと思います。でも、それでも私たちは毎朝起きて、できることをやっていくしかないんです。お互いを必要としているのは、今まさにこの瞬間だと思います。